Exploring Hagia Sophia, blue mosque, Grand Bazaar to Maiden’s Tower and Kadıköy on the Asian side

Our alarms went off just before sunrise — the earliest we’d managed all trip — because today we were determined to beat the crowds to the iconic sites of the Sultanahmet Square. The air still carried that faint coolness from the Bosphorus as we walked past shuttered shops and the echo of gulls. Street vendors were just setting up; one man balanced a stack of warm simit rings on his tray, their sesame crusts catching the first gold light.The Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya Camii) opens at 8:30 a.m. in summer, with lines forming by 8 — and arriving early makes all the difference. The building feels like the spirit of Istanbul itself: layered, luminous, and forever reborn. Built in 537 AD under Emperor Justinian I, it stood as the crown of Byzantine Christianity for nearly a millennium before becoming an Ottoman mosque in 1453, a museum in 1935, and again a mosque in 2020. Each era left its mark.From the front, the vast brick dome — 31 meters wide — seems to float above the nave, an engineering marvel by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus. Forty arched windows at its base pour in golden light that dances across centuries-old mosaics.

Visitors now follow a long, sloping ramp on the eastern side to the upper gallery, walking past Byzantine brick and Ottoman plaster — a tactile journey through history. At the top, the galleries open to breathtaking views of the interior. The North Gallery’s arched ceilings rest on marble pillars adorned with Islamic motifs over bright yellow stucco. Below, enormous wooden medallions inscribed with the names of Allah, the Prophet Muhammad, and the four Caliphs hang where Byzantine emperors once stood. Added in the 19th century under Sultan Abdülmecid, these symbols of faith now hover above the same marble galleries of the empire. The result is a seamless blend of Byzantine majesty and Ottoman devotion — a living testament to Istanbul’s layered soul.

From the inner narthex and upper gallery above the main entrance, you can see the forest of columns below and the mihrab curving toward Mecca — an elegant adaptation of the original Christian basilica for Muslim worship. Centuries of transformation have layered Islamic design over Byzantine architecture without erasing it, creating a harmonious blend where both faiths visibly coexist. The soaring dome, once crowned by a mosaic cross, now echoes with Qur’anic calligraphy, sunlight streaming through its windows like threads of gold.

Despite these changes, Byzantine mosaics still glow softly in the upper galleries. The Apse Mosaic of the Virgin and Child (c. 867), glimpsed from a corner of the south gallery, shows Mary enthroned with Christ against a golden background — one of the first images created after Iconoclasm. High above, faded seraphim with six wings still guard the dome, their golden faces bridging heaven and earth.

As you move to the south tympana ( right gallery), rows of Church Fathers, patriarchs, and angels appear in shimmering tesserae on the other side . One notable figure is Patriarch Ignatius the Younger, emphasizing theological reconciliation and the triumph of orthodoxy after centuries of Iconoclastic debate. Here you can see the famed Deësis Mosaic (c. 1261), created after the Latin occupation to mark the restoration of Orthodox worship. Christ Pantocrator stands at the center, flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, their tender, lifelike expressions pleading for humanity’s salvation — a masterpiece of Byzantine emotion and technique. Nearby, faint runic graffiti carved by Viking guards adds a surprising human touch. At the far end of the south gallery, imperial donor mosaics depict Emperor Constantine IX and Empress Zoe, and Emperor John II Komnenos with Empress Irene, each flanking either Christ or the Virgin Mary with the Child — stunning visual affirmations of imperial piety and continuity between the empire and the church.

We spent nearly an hour wandering the galleries, tracing the smooth grooves of marble balustrades worn by centuries of footsteps — emperors, sultans, and travelers like us. On the way out, the southwest vestibule mosaic caught our eye: the Virgin Mary enthroned with the Christ Child, flanked by Emperor Constantine offering a model of Constantinople and Emperor Justinian presenting a miniature of Hagia Sophia itself. Both wear jeweled imperial robes, symbolizing divine favor and imperial devotion. The golden mosaic embodies the Byzantine belief in the Virgin as protector of the city and a lasting tribute to the empire’s faith and artistry.

The Imperial Door, now accessible only to worshippers, once served as the ceremonial entrance for Byzantine emperors. Above it, a mosaic from around 900 depicts Christ enthroned, blessing with one hand and holding an open book inscribed with “Peace be with you; I am the light of the world.” An angel and the Virgin Mary flank Him, while below, an emperor bows in reverence — an act known as proskynesis. Scholars debate whether the figure represents Emperor Leo VI seeking forgiveness or a symbolic image of imperial humility before Christ, a fitting scene for rulers who once paused here to pray before entering the great nave.

When we finally stepped back outside, the square was alive with morning energy: vendors calling out, pigeons swirling above the fountain, and the tour groups arriving in waves. We found a bench facing the mosque, and got some simit from a vendor— mine with Nutella, Shay’s with cheese — and just sat watching Istanbul move around us. Next we turned toward the Blue Mosque (Sultanahmet Camii) — its six slender minarets rising gracefully against the brightening sky. The crowds had already thickened by the time we joined the entry line that curved along the courtyard. You can’t really visit Istanbul without seeing both Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque back-to-back — one a Byzantine jewel turned mosque, the other a pure expression of Ottoman confidence standing proudly across from it, like two mirrors reflecting centuries of empire.

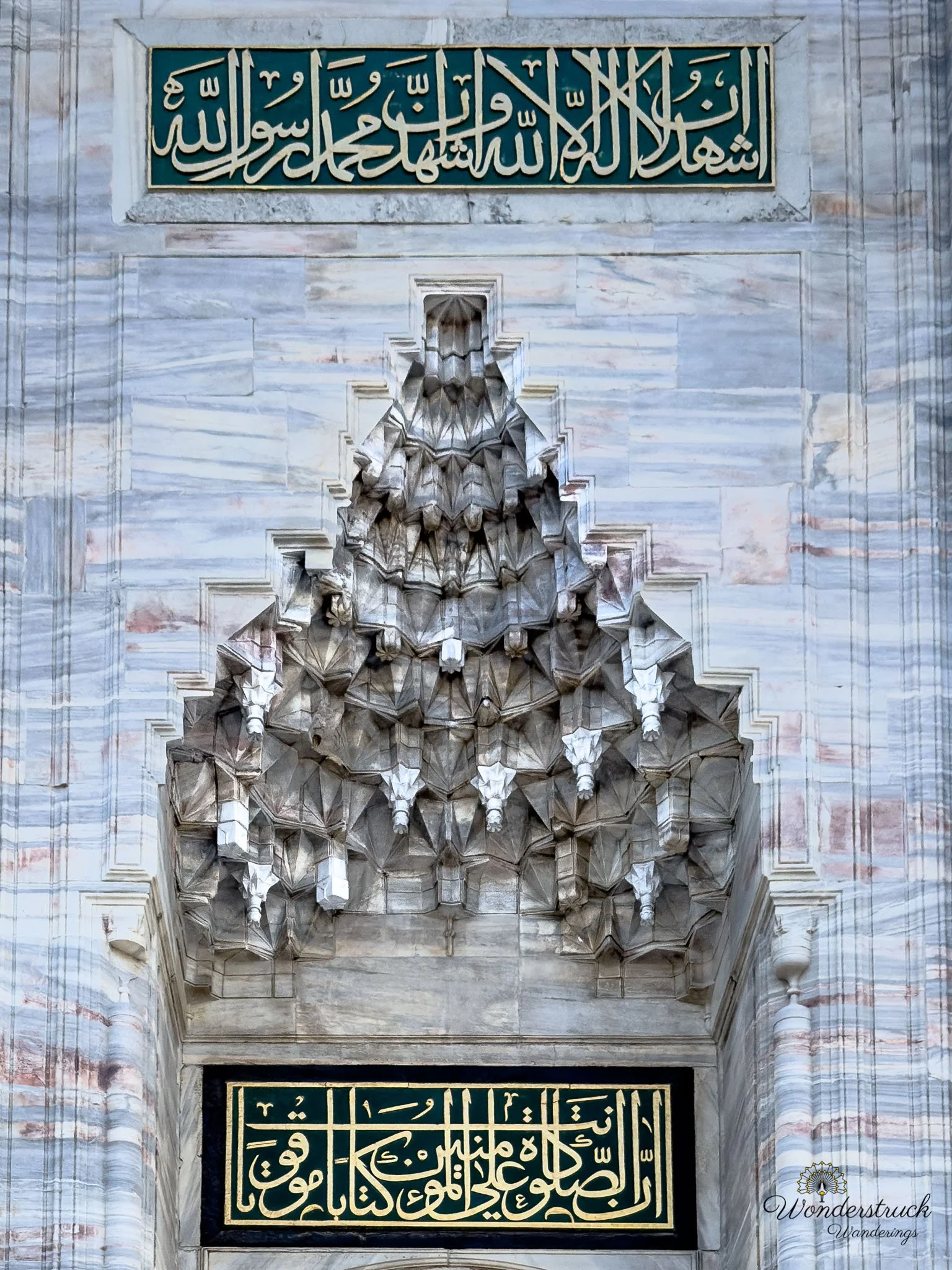

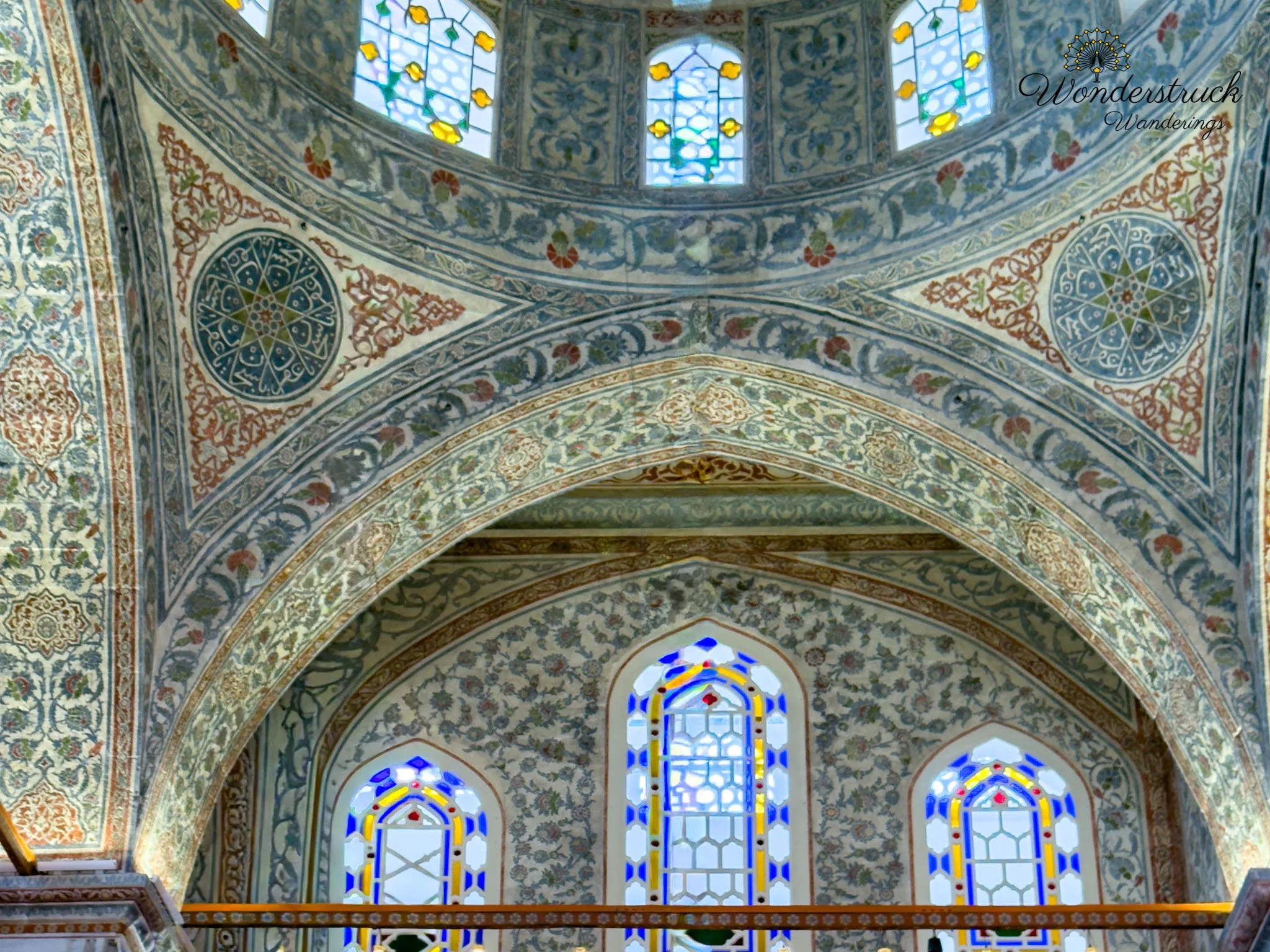

The Blue Mosque was commissioned by Sultan Ahmed I and completed in 1616 by the imperial architect Sedefkâr Mehmed Ağa, a student of the legendary Mimar Sinan. Built to rival Hagia Sophia’s magnificence, it became the first imperial mosque in Istanbul with six minarets. Stepping into the outer courtyard, we passed through a series of pointed arches framing the central ablution fountain. The sound of running water echoed softly beneath the stone arcade, and beyond the arches, the mosque’s cascading domes glowed in the morning light. Unlike the solid bulk of Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque feels lighter. Before entering, we removed our shoes and carried them inside. The moment we stepped onto the thick carpet inside, the world outside seemed to dissolve. The interior was awash in soft blue light, filtered through over 250 stained-glass windows. The name “Blue Mosque” comes from the İznik tiles (İznik çinileri) that adorn its walls — more than 20,000 of them, each hand-painted in intricate floral and geometric motifs. Shades of turquoise, cobalt, and sapphire ripple across the space like a sky frozen in pattern.Above us, the main dome soared 43 meters high, supported by four massive piers known as “elephant feet.” Gold calligraphy circled the arches, spelling verses from the Qur’an in elegant thuluth script, while chandeliers hung low, their glass globes glinting like captured stars. The mihrab — carved from white marble and set into a wall of Iznik tiles — glowed subtly under natural light, its orientation toward Mecca anchoring the space.

As we moved through the interior, we noticed the rhythm of prayer blending seamlessly with tourism — locals kneeling quietly on one side while visitors tiptoed on the other, with just a wooden barricade in between. Even amid the noise of feet and whispers, the mosque maintained its calm, a kind of architectural serenity that seems to hush you without command. We paused beneath one of the smaller domes, looking up to trace the arabesque patterns that radiated outward like celestial maps. It was mesmerizing to think how geometry here wasn’t just design — it was devotion turned into form, symmetry as a reflection of divine order. As we exited, sunlight poured into the courtyard again, glinting off the white marble and casting long shadows of the minarets.

Stepping back into Sultanahmet Square we found ourselves standing on what was once the Hippodrome of Constantinople, the grand chariot-racing arena that pulsed with the life of the Byzantine capital nearly seventeen centuries ago. It’s hard to imagine that beneath this calm open plaza, the roar of 100,000 spectators once shook the ground as horses thundered around the spina. Now, that same line of history runs quietly beneath our feet, disguised as park benches and flowerbeds. We began at the northern edge, beneath the elegant German Fountain—a gift from Kaiser Wilhelm II, its domed ceiling glinting with green and gold mosaics. Even in the stillness, the fountain carries an air of 19th-century diplomacy, a reminder that Istanbul’s story didn’t end with the fall of Constantinople—it kept layering itself, empire upon empire. From there, we followed the axis of the ancient track, stopping first at the Obelisk of Theodosius, the oldest thing in the square and perhaps the most astonishing. It once stood proudly at Karnak in Egypt before Emperor Theodosius I brought it here in the 4th century AD. The pink granite surface still shimmers faintly in the morning light, its hieroglyphs as crisp as the day they were carved. A few steps south, the Serpent Column coils upward, its bronze spirals weathered green with time. Hard to believe it was cast in Delphi to celebrate a Greek victory over Persia nearly 2,500 years ago, then carried here by Constantine to crown his new capital. Nearby, the Walled Obelisk—plain and patched but proud—anchors the southern end of the old arena. Today, the square belongs to a gentler rhythm. Tourists drift between monuments with coffee cups in hand, locals chat on benches, and cats patrol the shade like tiny emperors. Seagulls circle lazily overhead, their cries mingling with the hum of trams and the muezzin’s call—a new kind of chorus for this ancient stage. Standing between the Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque, it struck us how Sultanahmet Square is less a site to be seen and more a story to be felt—a rare place where time doesn’t just pass, it lingers, curling softly around you like the Istanbul breeze.

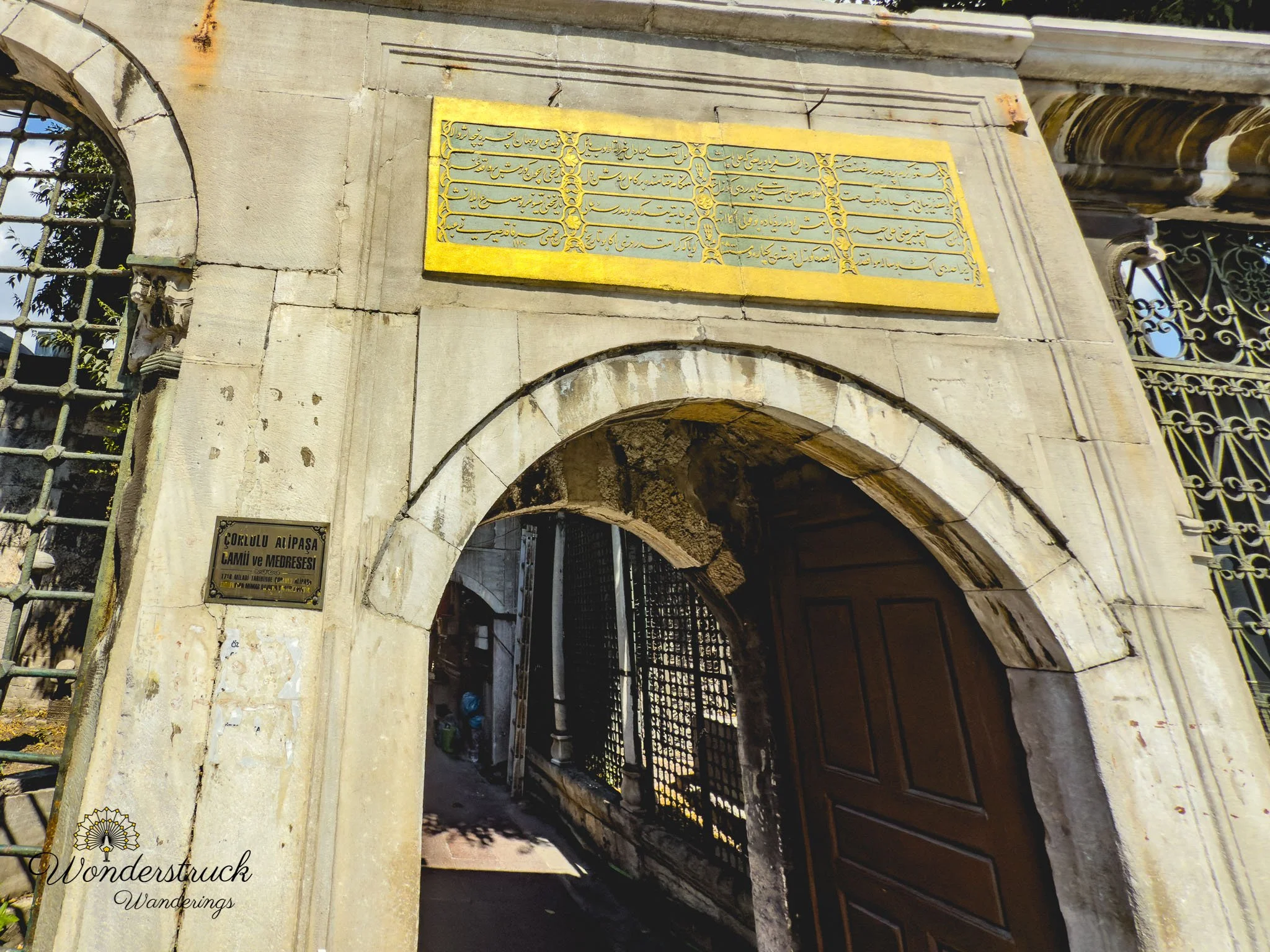

After the grandeur of Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque, we wanted a slower rhythm — a spot to sit, sip, and let the morning settle. A short walk down a shaded lane led us to Anadolu Nargile Çorlulu Ali Paşa Medresesi, a centuries-old tea and hookah lounge beside the Ali Paşa Mosque. The entrance was easy to miss — a narrow stone archway opening into a courtyard murmuring with quiet conversation.Built in the early 18th century by Grand Vizier Çorlulu Ali Paşa, this former medrese (Islamic school) has found new life. Its old classrooms are now cozy chambers with low wooden tables, cushions, and the drifting scent of apple and mint nargile. We settled beneath a weathered brick arch, the air thick with tobacco smoke and freshly brewed Türk kahvesi. Servers glided silently between tables balancing silver trays of steaming çay, the coals from hookahs glowing softly in the dim light. Our coffee arrived thick and rich in tiny porcelain cups — strong, grainy, and deeply aromatic. One of the café’s famously spoiled cats hopped up on the chair across from us, stretching lazily as if joining the conversation. There’s a rare comfort in places like this — where time slows, tea refills appear without asking, and the world outside feels very far away.

Outside, the sun had climbed higher, the streets were buzzing, and it was time to dive back into the city’s whirl — this time toward one of Istanbul’s great icons: the Grand Bazaar (Kapalıçarşı). Within minutes, we were funneled through the Nuruosmaniye Gate, one of its oldest entrances, and into a world apart. The noise of the streets faded, replaced by the hum of footsteps, the calls of merchants, and the soft clatter of metal and glass.Commissioned by Sultan Mehmed II in 1461, the Grand Bazaar has grown into a maze of 61 covered streets and over 4,000 shops — a living museum of Ottoman commerce. Domed ceilings pierced with skylights cast pools of light over stone-paved corridors, while every turn bursts with color: gold jewelry under chandeliers, cascading carpets, shelves of ceramics, spices, and mosaic lanterns glowing like captured stars. The air is thick with the scent of leather, rose oil, roasted nuts, and incense. “My friend! Good price! Where are you from?” calls out a shopkeeper — the soundtrack of the bazaar, warm and inviting.We wandered without hurry, pausing before displays of İznik ceramics in vivid turquoise and cobalt, each piece a small masterpiece. A nearby carpet shop lured us in with towers of Anatolian and Hereke rugs, soft and richly patterned. We left without a carpet but couldn’t resist a few smaller keepsakes — silver bracelets and blue nazar boncuğu charms.When we finally stepped back into the daylight, two hours had vanished. The Grand Bazaar does that — time dissolves into color, scent, and sound until you find yourself blinking, enchanted, and not quite ready to leave.

Just outside the bazaar’s gate, the Nuruosmaniye Mosque (Nuruosmaniye Camii) stood before us — elegant, serene, and perfectly placed to offer calm after the market’s chaos. Built between 1748 and 1755 under Sultans Mahmud I and Osman III, it marked a new era in Ottoman design, blending classical Islamic architecture with the European Rococo influences that were filtering into Istanbul. Its name means “The Light of Osman,” and light truly defines it.A broad staircase leads up to a marble courtyard surrounded by graceful arcades, each arch framing a sliver of sky. At the center, the şadırvan fountain murmurs as worshippers wash before prayer. Above the entrance, gold-leaf calligraphy glows on dark stone, inscribed with verses celebrating knowledge and enlightenment.Inside, the soaring 26-meter dome rests on four massive piers, opening the space to light that pours through 174 windows — one for each year since construction began. Sunlight drifts across the white marble, giving the mosque an airy, almost weightless beauty. The mihrab and minbar are carved from gleaming marble with delicate floral inlays, and gilded medallions bearing the names of the Prophet and the four caliphs shimmer overhead.

We headed to Güvenç Konyalı, a beloved spot for Konya-style cooking — slow-roasted meats, buttery breads, and the soulful flavors of central Anatolia. Tucked on a quiet street near Eminönü, the restaurant looked modest from the outside but felt instantly inviting inside: cool air scented with roasting lamb, white tablecloths, copper trays, and the comforting clink of tea glasses. Konya cuisine is all about patience — meat cooked for hours, recipes passed down through generations. We ordered the Konya Fırın Kebabı and İskender Kebabı, both unforgettable in their own ways. The Fırın Kebabı came on a copper platter, lamb roasted in a stone oven until it nearly fell apart, the edges crisped and the fat turned silky, served with soft flatbread to soak up every drop. The İskender Kebabı was pure theater — thin slices of döner piled over pide bread, drenched in tangy tomato sauce and sizzling butter poured at the table, then topped with creamy yogurt. Each bite was rich, smoky, and perfectly balanced. Before we left, our friendly waiter offered a peek into the kitchen. Upstairs, the taş fırın glowed amber as the chef pulled out trays of lamb so tender the aroma alone could make you hungry again. We couldn’t resist ordering one last dish — Kuşbaşılı Etli Ekmek, a long, thin flatbread topped with minced lamb, onions, tomatoes, and peppers, baked until crisp and golden. It was like a Turkish take on pizza — lighter, simpler, and utterly satisfying. With a cold ayran and a glass of çay to finish, it was the perfect close to the meal.

Full and content, we strolled down to the Eminönü Ferry Terminal, where the city pulsed with movement — ferries docking and departing, vendors roasting corn and chestnuts, and the hum of Istanbul’s daily rhythm echoing over the water. We used our Istanbul card for the Şehir Hatları ferry to Üsküdar, Istanbul’s quieter Asian side. For less than a few dollars, you get one of the best experiences in the city — a scenic voyage across the Bosphorus (Boğaziçi) that turns everyday commuting into poetry. As we pulled away from the pier, Istanbul unfolded around us like a living postcard. To our left rose the old city skyline — Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya Camii), Topkapı Palace (Topkapı Sarayı), and the Blue Mosque (Sultanahmet Camii) glowing in the afternoon light. To our right, the Galata Tower peeked over the rooftops of Karaköy, seagulls swooping low in hopes of snacks from passengers. The Bosphorus shimmered in layered shades of turquoise and steel, dotted with fishing boats, tankers, and private yachts gliding silently by. When we reached Üsküdar, the pace of life immediately changed. Gone were the heavy tourist crowds; in their place, local families, students, and fishermen leaning over the sea wall with lines trailing in the current. We’d come to see the legendary Maiden’s Tower (Kız Kulesi), one of Istanbul’s most iconic landmarks, standing small but proud on its rocky islet just offshore.

The walk from the ferry port to the Kız Kulesi Pier took about fifteen minutes along a seaside promenade lined with vendors and cafes. We had read online that the last ferry to the tower left at 4:30 p.m., so we hurried along, half-jogging the last stretch, only to find out that in true Istanbul fashion, timetables online don’t always reflect reality. The staff at the dock smiled and told us the boats leave every half hour — “no rush, we go when enough people come.” We laughed, catching our breath, thankful that our sprint wasn’t in vain. The ferry to Kız Kulesi cost about $10 round trip, while entry to the museum was $25 — thankfully covered by our Museum Pass İstanbul, which had already paid for itself. The ride was short, just five minutes across the shimmering Bosphorus. The Maiden’s Tower appeared ahead, gleaming white with its copper dome and Turkish flag waving proudly, standing like a sentinel between continents. Behind it, Istanbul’s skyline — domes and minarets — stretched across the horizon like a painted panorama.

On the tiny islet, we learned the tower’s story spans nearly 2,500 years. Built in Byzantine times as a watchtower, it later served as a customs post, lighthouse, quarantine station, and the heart of a tragic legend. According to myth, a Byzantine emperor built it to protect his daughter from a prophecy that she would die from a snake bite — yet fate found her anyway, carried in a basket of fruit. Ever since, the Maiden’s Tower has symbolized love, destiny, and the futility of defying fate. Architecturally, it’s modest — a stone base crowned by a wooden octagonal tower with a narrow balcony circling the top. Inside, the museum displays old maps, paintings, and relics chronicling its long service guarding the Bosphorus. From the viewing deck, the 360° panorama was stunning: the Asian hills behind us, the European skyline glowing in front, ferries tracing white wakes below like threads stitching two continents together.

When the afternoon sun grew harsh, we ducked into the small café inside. Over iced lemonade and a slice of cake, we watched the water sparkle through wide glass windows, seagulls drifting past in lazy arcs. It was one of those quiet travel moments that feel timeless — the city alive all around, yet you suspended in its stillness. After about an hour, we took the return ferry back to Üsküdar, still glowing with sun and sea spray, ready to dive deeper into Istanbul’s Asian side — toward Kadıköy, where locals eat, talk, and live at a rhythm entirely their own. Back on the mainland at Üsküdar, we called an Uber and soon found ourselves winding along the coastal road toward Kadıköy, one of Istanbul’s most vibrant, local-driven neighborhoods. If the European side is where the city performs, the Asian side is where it relaxes — the stage gives way to the living room. The energy shifts instantly: fewer tourists, more locals; fewer souvenir shops, more bookstores and record stores; less hurry, more life.

Our plan was to have a proper seafood dinner at Nisan Balık, a small, family-run restaurant tucked near the market. The kind of place where locals linger for hours, chatting over meze and clinking glasses of rakı, the anise-scented national drink that turns milky white when mixed with water. We asked the waiter for sole (dil balığı), and without hesitation he smiled and said, “Let me check the market.” Five minutes later, he returned, triumphant — “Yes, we have it!” He had literally run down the block to buy two freshly caught fish from the stalls. When the dish arrived, it was perfect on a plate — two large whole sole, lightly dusted with flour and pan-fried in olive oil until crisp and the flesh soft and buttery. A squeeze of lemon, a drizzle of olive oil, nothing more. The fish was so fresh it almost melted on the tongue, and the simplicity made it even better. We paired it with a few shots of Yeni Rakı, served in tall, narrow glasses with a jug of water and ice on the side. The ritual is part of the pleasure: pour the clear rakı, add a splash of water, watch it cloud into a pearly white swirl — they call it lion’s milk for its strength and purity. The flavor is anise-forward, sharp at first, then smooth, best sipped slowly between bites of seafood and meze. It’s not just a drink; it’s a conversation starter, a pause, a rhythm to dinner.

From there, we caught another Uber toward the Üsküdar waterfront, wanting to catch the sunset view of Kız Kulesi (Maiden’s Tower) from across the water. By the time we arrived, the promenade was already alive — families picnicking on the grass, couples sharing tea from thermoses, street vendors grilling corn and selling midye dolma (stuffed mussels) from silver trays. Children chased pigeons, musicians played saz and guitar under the streetlights. Later we learned it was a public holiday, which explained why everyone was out — an entire city reclaiming its evening by the sea. We found a spot on the seawall and watched as the sun dipped behind the skyline, the Galata Tower (Galata Kulesi) and Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya) silhouetted in fiery orange. The light spread across the Bosphorus like molten glass, turning pink, then lavender, then deep blue. As the last rays faded, the Maiden’s Tower lit up, its reflection shimmering in the dark water. It felt like the perfect full circle — we’d stood inside that tower just hours earlier, and now we were watching it from afar, glowing like a lantern between continents.

As the evening deepened, we walked slowly back toward the ferry pier, savoring the last sights. Around 8 p.m., we caught the ferry back across to Eminönü, the city skyline now a ribbon of gold.On the walk back to our hotel, we made one last, inevitable stop — Faruk Güllüoğlu, that temple of pistachio baklava and Turkish tea (çay). We ordered a small plate of warm baklava, syrup still glistening, and a couple of cups of tea. Back at the hotel, we packed our suitcases for our 6 a.m. flight. It was the perfect ending — not dramatic or grand, just deeply content. The kind of day that reminds you why you travel at all.