Exploring Galata tower, Dolmabahçe Palace, Ortaköy Mosque and Sultanahmet sunset

Another slow, late wake-up — the kind that feels earned after days of walking and wonder. The light filtering through our hotel curtains was soft and golden, the kind that makes Istanbul look like it’s been painted in honey. We lingered over our morning routine before heading up to the rooftop café for breakfast. By now, the ritual felt familiar: strong Turkish coffee, crusty simit, bowls of olives, feta, honeycomb, and tomatoes glistening in olive oil. From the terrace, we could see the Galata Tower (Galata Kulesi) rising above the old rooftops like a sentinel — part lighthouse, part storyteller, keeping watch over the centuries. The seagulls circled lazily above the Bosphorus, and the air smelled faintly of sea salt and baked bread. After breakfast, we made our way to the cobblestone street that stretches out directly in front of the tower — the one that appears on almost every postcard and Instagram feed. It’s the quintessential Istanbul photo: narrow lane, colorful old buildings leaning slightly inward, and the tower framed perfectly in the background. We waited our turn, weaving between couples trying to get that same shot, and laughed at the quiet chaos of it all. The morning was already warming up, and street vendors were setting up their displays — evil-eye charms, hand-painted ceramics, fridge magnets and more..

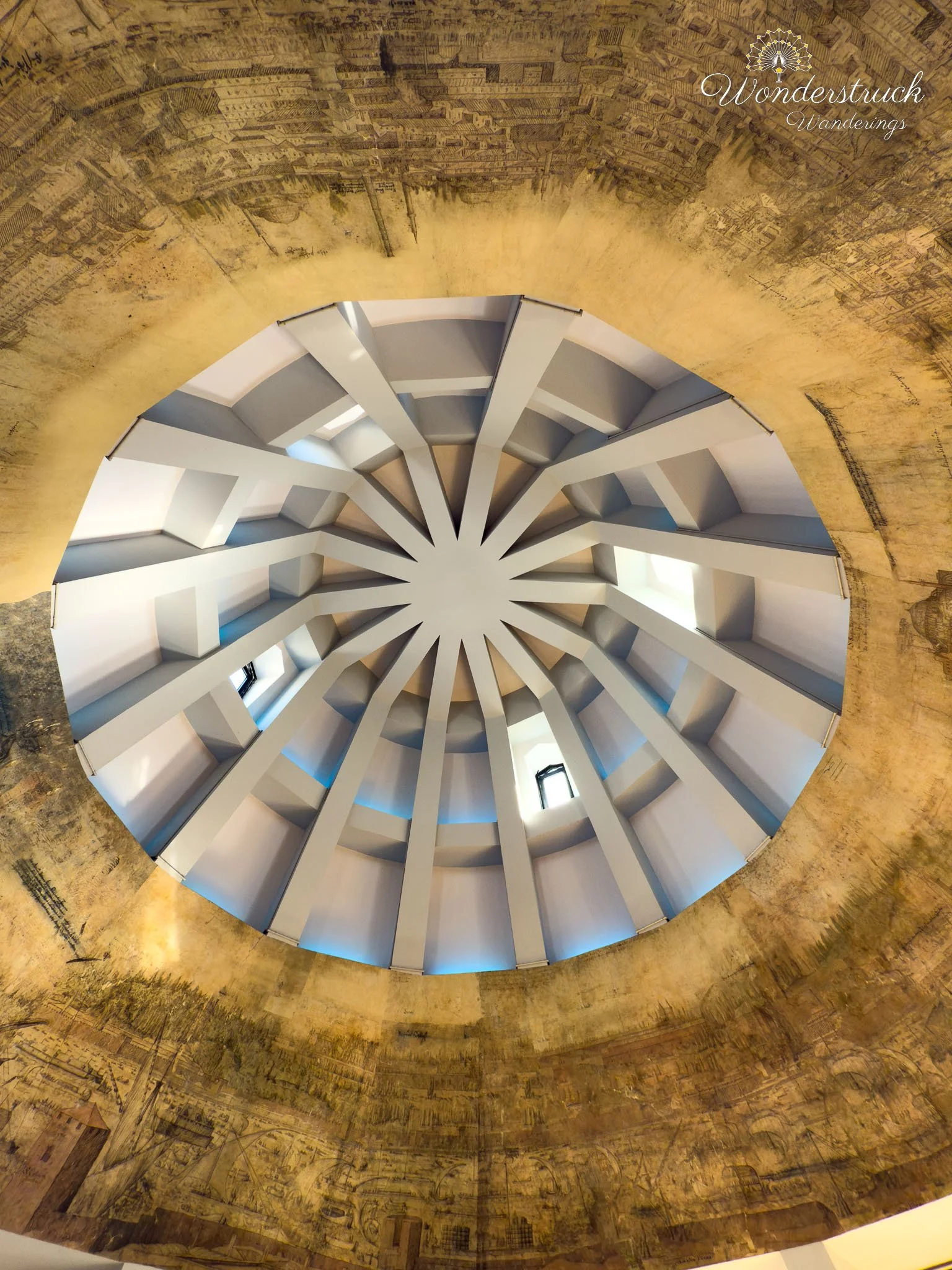

The line to go up the tower was starting to build up.. Entrance is included in the Museum Pass İstanbul, but you still have to queue with everyone else. Built in 1348 by the Genoese as part of their fortifications, Galata Tower is one of Istanbul’s most enduring landmarks. Originally named the Christea Turris (“Tower of Christ”), it was later used as a fire-watch post during the Ottoman period — the city’s earliest warning system before telegraphs and sirens. Over the centuries, it has survived earthquakes, fires, and sieges, and yet still stands tall at nearly 67 meters, its conical roof now a familiar shape in the city’s skyline. It was once the tallest structure in the world. I got its first glimpse while playing Assassin's Creed where the tower looms above Constantinople, stretched endlessly, a maze of domes and rooftops— a perfect perch for history’s invisible watchers to dive from. The tower’s architecture is simple— thick stone walls twitch a dome shaped top, romanesque windows framed with pointed arches, and a narrow spiral staircase that feels almost medieval. One of the tower’s most fascinating stories is that of Hezarfen Ahmed Çelebi, the 17th-century Ottoman polymath who, according to legend, leapt from this very tower wearing homemade wings and flew across the Bosphorus to Üsküdar. Whether true or not, the story has become part of Istanbul’s mythology — a symbol of ambition and imagination. On one of the upper floors, there’s a small 3D animation exhibit that dramatizes his flight, complete with whirling wind and soaring seagulls. It’s kitschy but charming — a nod to the dreamers who always try to take flight.

At the top the observation balcony, a narrow ring of stone barely wide enough for two people to pass, was crowded but worth every jostle. The panoramic view from here is pure Istanbul — domes and minarets scattered across the horizon, ferries gliding along the Bosphorus, the Golden Horn (Haliç) shimmering in the sunlight, and the vast expanse of rooftops blending old and new. From one side, the silhouettes of Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya) and the Blue Mosque (Sultanahmet Camii) rose above the historic peninsula; from another, the modern skyline stretched beyond the Galata Bridge. One floor below, we peeked through narrow windows offering smaller, more intimate glimpses of the city — like fragments of a painting. You can trace almost every major landmark from here, from the sprawl of Topkapı Palace (Topkapı Sarayı) to the gleaming bridges that connect continents. Back on the ground, the streets around the tower buzzed with life we picked up a few souvenirs — a couple of fridge magnets, a string of nazar boncuğu (evil-eye) charms, and from a tiny hole-in-the-wall shop down an alley, an intricately embroidered needlework jacket that looked like something out of an Ottoman portrait.

By late morning, the sun had turned fierce, and we decided it was time to move on to our next stop — Dolmabahçe Palace (Dolmabahçe Sarayı), the empire’s final seat of glory by the water. Back at our hotel we packed our bags and left them with the hotel reception, as it was checkout day .We called an Uber, and within minutes we were winding downhill toward the Bosphorus. The 20-minute ride cost about twelve dollars and the driver dropped us right in front of the palace entrance, between the graceful Dolmabahçe Clock Tower (Dolmabahçe Saat Kulesi) and the elegant Bezm-i Âlem Valide Sultan Mosque (Bezmialem Valide Sultan Camii)—often called the Queen Mother’s Mosque. By 10 a.m. the heat was already building; the marble glared white under the sun. We walked through the garden gate past a fountain and manicured lawns, the ticket office tucked discreetly to the left. Unlike Topkapı, this palace isn’t included in the Museum Pass İstanbul, so we bought separate entry tickets and joined the small queue forming under the trees. Stepping beyond the gate felt like entering another era. The Selamlık Garden unfolded in front of us—a meticulously arranged landscape where European symmetry met the Ottoman soul. White marble balustrades lined the pathways, rose beds spilled over with color. The scent of linden trees mingled with the sea breeze from the Bosphorus just beyond the gilded fences. Through gaps in the foliage, the palace shimmered—its pale façade mirrored in the water, a grand symphony of Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassical design layered over Ottoman foundations.

Construction of Dolmabahçe Palace began in 1843 under Sultan Abdülmecid I, who wanted a residence that reflected the empire’s modern aspirations. “Dolmabahçe” literally means “filled-in garden,” a nod to the reclaimed bay on which the palace now stands. The result was breathtaking: a residence of 285 rooms, 46 halls, six baths, and 68 toilets, stretching for nearly 600 meters along the water’s edge. The architect, Garabet Balyan, and his son Nigoğayos Balyan, drew inspiration from Versailles and the palaces of the Loire, yet wove in Ottoman sensibilities—wide eaves, arabesque plasterwork, and a rhythm of domes that softened the European lines. The Selamlık, or ceremonial wing, was where the Sultan received ministers and foreign dignitaries. Its entrance alone announces power: twin staircases curving toward bronze doors, Corinthian columns gleaming like ivory, and above them the tughra—Abdülmecid’s imperial monogram—etched in gold leaf. Standing there, it’s easy to imagine the carriages arriving, wheels crunching on gravel, attendants in crimson fez hats bowing as the guests stepped out.

Photography inside is strictly prohibited, so what remains is memory—impressions of light and texture. Crossing the threshold, we entered the Medhal Hall (Medhal Salonu), a cavernous reception room where foreign officials once waited for the audience. Sunlight streamed through crystal chandeliers, scattering rainbows on marble floors polished smooth by centuries of footsteps. On the fireplace mantel, Abdülmecid’s tughra glowed faintly in the half-light; even the gilded Boulle-style side tables, inlaid with brass and tortoiseshell, seemed to carry whispers of diplomacy. The interiors were done by Charles Séchan, the French stage designer behind the Paris Opera. Everywhere, his signature: ceilings painted with rococo medallions, gilded stucco scrolls, and chandeliers that looked like frozen waterfalls. Rooms facing the Bosphorus were reserved for grand viziers and visiting envoys; those looking inland housed palace administrators—a geography of hierarchy written into architecture.

We moved through cool corridors to the palace’s most photographed wonder, the Crystal Staircase (Kristal Merdiven). Two sweeping flights of Baccarat crystal steps curved upward beneath a domed skylight, their balustrades of mahogany and brass glinting in the sunlight. Upstairs lay the Ambassadors’ Hall (Elçiler Salonu), its smaller salons hung with seascapes by Ivan Aivazovsky, the Crimean-Armenian painter who became a favorite of the Ottoman court. His canvases—ships tossed in stormlight, moonlit harbors, the Bosphorus at dawn—looked almost alive against the palace’s pale walls. Every room told a different story through color. The Red Room (Kızıl Salon) pulsed with warmth—crimson velvet, gold tassels, and draperies heavy enough to silence a whisper. The Privy Chamber (Mahfel Odası), used for religious ceremonies and royal weddings, glowed under gilded domes supported by marble columns veined like clouds. And the Sultan’s private Bath (Hünkâr Hamamı), carved entirely from white marble and alabaster, radiated tranquility—the geometric play of domes and light turning water into poetry. The Blue Hall (Mavi Salon) connected the ceremonial rooms, its mirrored walls multiplying the glint of chandeliers. At its far end we reached Atatürk’s Room—a small, sun-washed chamber where the founder of modern Turkey spent his final days. His bed remains draped with the national flag; all clocks are stopped at 9:05 a.m., the moment he passed on November 10, 1938. Nearby, the Pink Hall (Pembe Salon) offered softer notes—rose walls, gilt trim, and French furniture that once belonged to the Queen Mother (Valide Sultan). And then came the crescendo: the Ceremonial Hall (Muayede Salonu). The numbers alone stagger imagination: a dome 36 meters high, 56 columns, a 124-square-meter Hereke silk carpet, and at its heart a Bohemian crystal chandelier weighing 4.5 tonnes with 750 lamps.

By the time we emerged into the sunlight again, the marble gleamed like ice under the noon heat. We crossed the courtyard toward a small café near the Harem entrance, ordered tiramisu and icy lemonade, and sat under the blessed hum of air-conditioning, grateful for shade before continuing our exploration of this palatial world. Once we’d cooled off, we crossed over to the neighboring National Palaces Painting Museum (Milli Saraylar Resim Müzesi) — housed inside the elegant Crown Prince’s Residence (Veliaht Dairesi), just a few steps from the main palace grounds. It’s easy to miss; most visitors rush from the grand halls of Dolmabahçe straight to the Bosphorus promenade, unaware that an equally rich story waits right next door. But for us, this museum was an unexpected highlight — quieter, cooler, and filled with art that whispers rather than shouts. The building itself was designed in the late 19th century as the private quarters for the heir apparent to the Ottoman throne. Architecturally, it mirrors Dolmabahçe’s exterior grace — French neoclassical columns, delicate ironwork balconies, and large arched windows that let the Bosphorus light flood the rooms. Inside, more than 200 paintings line the high walls — portraits, landscapes, seascapes, and domestic scenes spanning the late Ottoman and early Republican eras. The collection tells a visual story of transformation — how Ottoman art evolved as Western influence began to blend with local tradition. The early galleries are filled with formal portraits of sultans, their gazes steady and solemn. One that caught my eye was a regal depiction of Sultan Abdülaziz, painted by Pierre-Désiré Guillemet, a French artist who spent decades in Istanbul. In another room hung the luminous works of Şeker Ahmet Paşa, one of the first Ottoman painters to study in Paris. His landscapes and still lifes felt serene, his brushstrokes looser and more atmospheric than his predecessors’. You could almost feel the gentle sway of the trees or the glint of sunlight off a boat’s hull. Then came Osman Hamdi Bey, the artist-scholar whose name has become synonymous with the Ottoman art revival. His famous painting The Tortoise Trainer (Kaplumbağa Terbiyecisi) isn’t housed here — it’s at the Pera Museum — but several of his other works are, and they carry the same signature duality: Ottoman subjects framed through Western composition, introspection meeting modernity. A few halls away, we found the Impressionist touch of Halil Paşa, another Paris-trained artist who brought back a love for open air and movement. His seascapes shimmered with light, waves catching sun in fleeting brushstrokes. Nearby, Hoca Ali Rıza’s paintings offered intimate portraits of Istanbul’s wooden neighborhoods — crooked houses, quiet streets, everyday moments that now feel like glimpses of a vanished world. One hall, though, belonged entirely to the sea. This was the domain of Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky, the Crimean-Armenian painter beloved by the Ottoman sultans. His massive maritime canvases stretched across the walls — ships battling storms, moonlit Bosphorus views, and golden horizons that seemed to glow from within. Legend says Sultan Abdülmecid was so enchanted by his work that he commissioned more than thirty paintings, many once displayed in Dolmabahçe’s grand salons. The later rooms transitioned into the early Republican period, where Turkish painters like İbrahim Çallı and Hikmet Onat embraced a more modern sensibility. Their colors were brighter, their strokes bolder, their subjects distinctly new — schoolgirls, laborers, harbor scenes — marking the visual shift of a nation stepping into the 20th century.

Leaving the quiet elegance of the Painting Museum, we walked back through the garden toward the entrance of the Harem Dairesi, the private living quarters of the Sultan and his family. The transition from the Selamlık’s ceremonial grandeur to the domestic calm of the Harem felt immediate — like stepping from a ballroom into a family home. Even the air seemed different here, softer and perfumed with cedar and age. In Ottoman times, this part of the palace was heavily guarded; only the Sultan, the Valide Sultan (his mother), and select attendants could move freely within. Visitors like us can only imagine the rhythms of life that once pulsed through these rooms — the whispers, the laughter, the music that carried through the marble halls.

We entered first into the Hall of the Royal Women (Kadın Efendiler Salonu), the social heart of the family quarters. This bright chamber once hosted celebrations for religious holidays, children’s birthdays, and family gatherings. Light poured through tall arched windows, warming the parquet floors and reflecting off crystal chandeliers that swayed slightly in the breeze from the Bosphorus. The furnishings were elegant but not ostentatious — upholstered divans, mother-of-pearl inlaid tables, and fine carpets whose colors had mellowed into soft golds and blues. It felt lived-in, not staged. Beyond it, narrow corridors led to the Harem Hamamı, the smaller bathhouse reserved for the Sultan’s wives and daughters. Compared with the Sultan’s marble-and-alabaster bath in the Selamlık, this one felt almost intimate. The dome above was perforated with star-shaped glass windows that let in scattered light like a constellation. The next room, the Japanese Salon (Japon Salonu), was an unexpected one — a gift from Japan during the late 19th century, filled with lacquered furniture, folding screens painted with cranes and chrysanthemums, and silk panels embroidered with gold thread. The fusion of Ottoman and Far Eastern aesthetics felt surprisingly harmonious. Among all the rooms, the suite of Pertevniyal Valide Sultan, mother of Sultan Abdülaziz, stood out most. Her apartments exuded a refined femininity — pastel-colored walls trimmed with gilt, delicate floral motifs, and furnishings in the French Rococo style that was so fashionable in Paris at the time. The result was graceful rather than lavish, more like a Parisian salon than an imperial chamber. From the windows, the Bosphorus glimmered in the afternoon sun.

By the time we left Dolmabahçe, the midday sun had grown relentless, shimmering off the Bosphorus like scattered glass. We hailed another Uber and rode just a few minutes up the coast to one of Istanbul’s most photographed neighborhoods — Ortaköy, a lively waterfront district that feels equal parts postcard and playground. The Ortaköy Mosque (Büyük Mecidiye Camii) sits right at the edge of the water, its white marble façade glowing against the turquoise of the Bosphorus and the sleek arc of the 15 July Martyrs Bridge (15 Temmuz Şehitler Köprüsü) rising just behind it. The mosque was commissioned by Sultan Abdülmecid I — the same visionary who built Dolmabahçe — and completed in 1856 by the Balyan family of architects, the empire’s go-to builders for anything magnificent. Its design blends Ottoman grace with Neo-Baroque exuberance: tall arched windows flooding the prayer hall with sunlight, delicate stucco floral carvings along the cornices, and a central dome ringed with inscriptions in fine calligraphy. From the outside, it feels airy and regal; inside, it’s intimate, filled with golden light that dances across pink marble columns. The way the structure hugs the water gives it a dreamlike quality — a mosque that almost seems to float when the tide rises. We finally reached the very spot we’d planned to visit for sunrise on our first morning but never managed to wake up for. The light now was harsher, but still spectacular — the mosque gleaming like porcelain, the bridge arching above it in perfect symmetry. We took our photos, laughed at how many tourists were trying to get the same angle, and then gave in to our hunger.

Lunch was at a nearby waterfront restaurant called Yelken Cafe, one of the many open-air spots lined along the promenade. The view was postcard-perfect — the mosque to one side, ferries sliding across the Bosphorus, and cats weaving between tables hoping for scraps. We ordered a Turkish kebab platter, a colorful spread that arrived sizzling: Adana kebab, minced lamb grilled with chili; Şiş kebab, tender cubes of chicken and beef on skewers; and Köfte, small, juicy meatballs flavored with cumin and parsley. Served with rice, grilled tomatoes, flatbread, and a side of smoky yoğurtlu ezme, it was hearty and satisfying, though a bit overpriced — a reminder that scenic spots often charge for the view as much as the food. They only accepted cash, and the bill needed a quick double-check, something worth keeping in mind in tourist-heavy areas. Still, after hours of walking palaces, every bite felt like a small victory. After lunch, a vendors called out playfully, holding out trays of Turkish ice cream (dondurma), and of course, we couldn’t resist. The show began immediately: the vendor, dressed in a traditional vest and fez, twirled the long-handled metal scoop like a magician’s wand, ringing his bell and teasing us with a cone he’d never quite let go of. Turkish ice cream, made from goat’s milk and mastic, is elastic and chewy, nothing like Western varieties — it stretches, twirls, and refuses to melt easily in the sun. The whole performance is part of the ritual; you don’t just buy ice cream here, you earn it with laughter and good humor. Ours was pistachio — creamy, dense, and worth every second of the playful torment. We traced our way back to the main road. Across from the mosque we passed through a long row of vendors selling kumpir — baked potatoes turned into full meals. Each one was split open, mashed with butter and kaşar cheese, then piled high with toppings: olives, pickles, corn, sausages, peas, and anything else you could imagine. The stalls were colorful and fragrant, each vendor calling out promises of the “best kumpir in Istanbul.”

We hailed another uber to get back to our hotel before loading up our luggage to move on to the next location, the historic heart of the city. Our next stop was the Seven Hills Hotel.The Seven Hills Hotel is one of the most photographed stays in Istanbul — perched right in the heart of Sultanahmet Square, halfway between Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya) and the Blue Mosque (Sultanahmet Camii). The location couldn’t be more central; step outside, and you’re walking through a thousand years of history. Travelers book it for one thing above all — the rooftop terrace, where two empires and three continents seem to meet in one sweeping view. At the reception, check-in was effortless, and the staff greeted us with a welcome drink. Our Hagia Sophia View Deluxe Room was surprisingly spacious for such a prime location: polished wood floors, carved furniture, and windows that framed the domes of Hagia Sophia like a living postcard.After dropping our bags and splashing our faces with cool water, we headed straight out again to make the most of the remaining daylight.

Just a short walk down the square brought us to one of Istanbul’s most atmospheric sites — the Basilica Cistern (Yerebatan Sarnıcı). Built in 532 AD under Emperor Justinian, this underground water reservoir once supplied the Great Palace and surrounding areas. The name “Yerebatan” means “submerged” — a fitting description for this hidden world beneath the city’s surface.

After buying our tickets we descended the damp stone staircase, the city above seemed to vanish. The air cooled instantly; a faint smell of moss and old marble replaced the heat and spice of the streets. Inside, hundreds of ancient columns rose from shallow pools of water, their reflections shimmering under the glow of ever-shifting lights. The cistern’s vaulted ceilings seemed endless, each arch catching the artificial lighting's color changes — deep blue fading into crimson, gold melting into violet.

Though the crowds were thick at first, we navigated quickly to the iconic spots — the Medusa heads, repurposed as column bases in the northwest corner. One is placed sideways, the other upside down, their expressions serene even in inversion. We moved fast, snapping photos where we could.Where ever you look you see — rows of marble pillars fading into infinity, the rippling water catching flecks of light like starlight underwater. There’s something almost spiritual about the space, a calm that feels ancient. As the closing hour approached, visitors began trickling out, leaving the cistern quieter and more ethereal. For about fifteen minutes, it was magic — just us, the columns, and the echo of time. The staff were kind, gently ushering us toward the exit without rush, letting us take a few last photos. Climbing back up into the open air felt like resurfacing from a dream.

We returned to the Seven Hills rooftop, the reason we’d booked the hotel in the first place. The terrace unfolded like a stage — Hagia Sophia gleaming on one side, the Blue Mosque rising opposite, and the Bosphorus glittering faintly in between. As we found a corner table, the azan (call to prayer) began to ripple across the city, echoing from one minaret to the next. The overlapping melodies — deep, resonant, and hauntingly beautiful — filled the air. The sunset unfolded slowly, painting the domes and rooftops in molten gold, then rose, then indigo. As night fell, the city lights flickered on one by one, and Istanbul transformed once again. We ordered a plate of grilled octopus in garlic butter, paired with Yeni Rakı, the anise-flavored spirit that tastes like liquid nostalgia. The octopus was tender, smoky, perfectly cooked — though, as we’d been warned, the prices were as lofty as the view. Still, sitting between two of the world’s most iconic monuments, watching the last light fade, it was hard to complain.

When the sky finally darkened and the city below turned to gold and silver, we finally tore ourselves away from the rooftop. The evening breeze had cooled the streets, and Sultanahmet Square felt alive again — couples strolling hand-in-hand, the smell of roasted chestnuts drifting through the air. Our first stop was Şehzade Kebab (Şehzade Erzurum Cağ Kebap) — a place so famous that the crowd and its aroma pulls you in long before you reach the door. Inside, the menu was refreshingly short: cağ kebab, a style from Erzurum where marinated lamb is stacked horizontally on a skewer and slowly roasted over wood fire. The chef carved thin slices directly onto the plate, each one glistening with smoky fat. Served with warm lavash, onions, and a sprinkle of sumac, it was pure simplicity done perfectly — juicy, slightly charred, and deeply satisfying. When a restaurant sells only one or two dishes, you know they’ve mastered them, and Şehzade proved that rule beyond question.

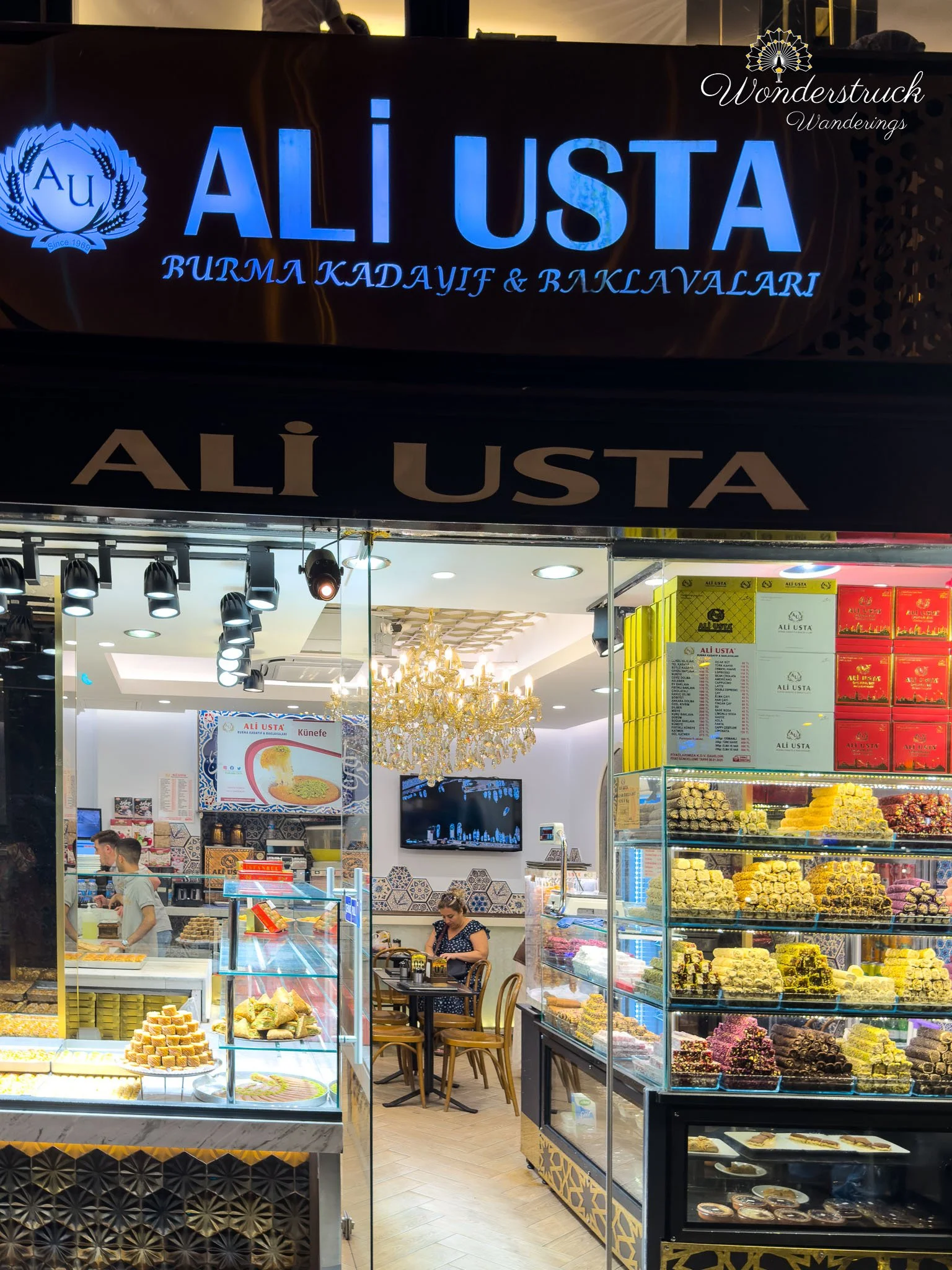

Afterward, craving for our nightly desert ritual , we walked a few blocks toward Hafız Mustafa 1864, one of the city’s most legendary patisseries. Its windows glowed like treasure chests — trays of baklava, şöbiyet, kataif, and glossy lokum stacked in neat, jewel-toned rows. The café upstairs was packed, so we decided to get a few boxes to go.Turkish delight (lokum) gleamed under glass in every color imaginable: rose, lemon, pomegranate, mint, even coffee. The clerk offered us samples — chewy, fragrant, rolled in powdered sugar that left our fingers dusted white. It’s impossible not to smile when something so small tastes that purely joyful. We packed some for home as well. We moved to Ali Usta, a small café dessert store next door. We sat inside with glasses of steaming Turkish tea (çay) in tulip-shaped glasses. We sipped our tea and shared the last pieces of pistachio baklava before making our way back to the Hotel, the cobblestones still warm from the day’s sun, we looked up to see Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque facing each other across the square, their domes glowing under the moonlight. Tomorrow, our last full day in Istanbul, will take us through these greatest landmarks.